I said as much when writing about Dumbo last month at the newsletter, but in the run-up to the launch of Disney+ in the fall of 2019, there were rumors that the 1941 film would be edited to remove “the Jim Crow scene”, AKA the scene in which a group of crows that are outlandish and offensive stereotypes of Black men sing “When I See an Elephant Fly”. I remember reading the purported exclusive from one of many Disney fansites, and finding its conclusion to be almost (but not quite) as ridiculous as the crows themselves. The issue was not whether or not those characters are racist stereotypes (they are), or if the scene is offensive (it is). What I kept getting stuck on was how drastically the story of Dumbo would be altered with the removal of the crows.

It’s only because of those crows that Jumbo, Jr. the elephant realizes that he can fly, literally. The crows may be doubtful (and for good reason), but if not for them mocking Jumbo, Jr. and Timothy Q. Mouse, the image of an animated flying elephant wouldn’t have ensued. To remove the crows would, unfortunately, amount to removing the crux of the whole movie. As I recall, I made points to this effect in the spring of 2019 on Twitter (you remember when it wasn’t called X? Fun times), and some people got very mad at the implication that a random fansite wasn’t a reliable source, though I wonder if they recalled that reaction when, in the fall of 2019, Dumbo was available in full as it was originally created.

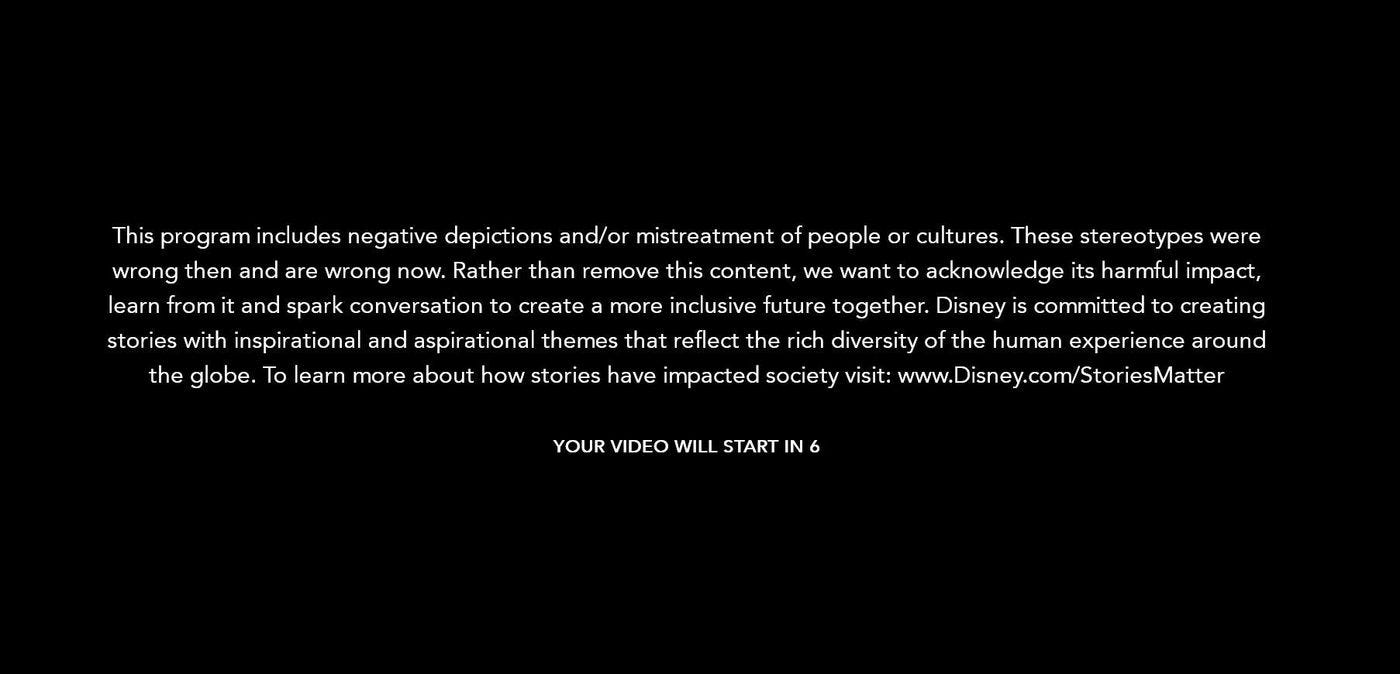

Almost a year later, Disney did make a change to Dumbo and a few other films, adding a title card that you’ve probably seen at least once or twice on Disney+.

Stories matter at the Walt Disney Company, and it’s no surprise. They are the backbone of the studio, and not just the stories themselves; it’s the act of telling stories that is often as critical as the stories themselves. I wish I could tell you that the website linked in that title card or the YouTube video linked on that same page are as crucial. To my eye — and I have visited the site a few times over the last few years out of curiosity — they’re not only drops in the veritable bucket, but they are woefully lacking in something else that matters: context. Context matters, and so does timing. Films like Dumbo, Peter Pan, and “Aristocats” (that is how the 1970 animated film is identified on the Stories Matter website, inexplicably omitting the word “The” at the start, a mistake they have kept on the site since it was launched) were offensive and stereotypical long before Disney+ launched. But these title cards weren’t there on Day One. They were added in the fall of 2020. A few months beforehand, Disney made another bombshell announcement: they were shutting down the immensely popular Splash Mountain attraction in Disneyland and Walt Disney World and replacing it with a ride themed to the wonderful animated film The Princess and the Frog.

To the untrained, context-free eye, the eye of someone who managed to avoid their cultural history and awareness, it might have been truly baffling that Disney would shut down Splash Mountain. Here was an attraction designed well by Imagineers, blending a classic dark ride with a log flume. Here was an attraction that never wanted for long lines of crowds. Why close a popular attraction, this unaware person may ask.

Because it’s based on the 1946 film Song of the South.

I am going to make the wild assumption here that if you’re reading this essay, you are at least aware of Song of the South, but how you and I define “aware” may differ. You may have seen Song of the South, either via bootleg copy or even in theaters. (The film was last re-released in American theaters in 1986.) You may have seen clips of the film on YouTube or in various Disney compilations over the years; because portions of the film are animated, those portions were kept around in official formats for years beyond the live-action sections that make up the bulk of the picture. Or you may just know the film by its reputation: that it’s an unforgivably racist depiction of Black people circa the Reconstruction Era in Georgia.

I do want to put a pin in the Splash Mountain part of this broader topic, because it’s important to talk about the movie in detail. I will clarify here (for anyone who may need the specific clarification) that I’m not going to mount a defense of this movie aside from the following sentence. It is a fascinating thing to discuss, some of its songs are arguably very catchy, and the animation is pretty impressive especially considering that the mid-1940s were a very lean time for Disney animated pictures. Song of the South is also a very racist film, and potentially even more painful to watch because you can mount the case that the White people who made this movie did not think they were being racist. This may not be as cruel a depiction of Black people as what you would find in D.W. Griffith’s Birth of a Nation, but…well, that’s a pretty low bar to clear, isn’t it?

I should note one addition to the reputation that Song of the South has. It’s not just that the film is correctly perceived as embarrassingly racist, it’s that the film is so racist that it has never been released by Disney on VHS, DVD, Blu-ray, or streaming. For a long time, there was a log-flume-shaped wrinkle in that reputation, because if the film was so racist that Disney never wanted it to be seen by the viewing public, then…well, why did it inspire a theme-park ride literally decades after its release?

Back in 2018, I wrote a book about Disney films and racism, and explored Song of the South in some depth there. (An aside: I know it doesn’t matter much, but please be aware that “Was Walt Woke?”, the headline at the top of the description in that webpage is…not something I came up with.) The Stories Matter website and the related title cards are a baby step in the right direction, and one I attempted to push towards in the book. That Song of the South is racist is pretty close to an immutable fact, no matter how loudly some folks shout. (Somehow, their angry petitions to save Splash Mountain didn’t work. Who’d’ve guessed.) But for a while, I could not help but wonder why Song of the South got this treatment, where films like Peter Pan and Dumbo and Lady and the Tramp and The Aristocats got splashy home-media releases.

I say “for a while” because context and timing matter. The book I wrote was published in 2018; not exactly a utopian period in American history, of course, but a period less intensely fraught than, say…well, the murder of George Floyd at the hands of a police officer, one of many such cases of police brutality that led to a worldwide wave of protests against systemic, institutional racism that has existed for centuries. I mention the George Floyd murder because while Disney sources said (in articles like the New York Times piece about the Splash Mountain closure linked above) that event did not inspire the announcement…I mean. C’mon. Timing here does not feel accidental, and how could it?

How many films can bear the weight of such controversies? Even if some Disney film potentially could, Song of the South cannot. (I do want to note briefly that one thing I pointed out in the book is alive and well: for all of Disney’s famous litigious nature, it is easier than you might think to watch Song of the South. Say, if you visited a site like…oh, I don’t know, YouTube. And if you typed in “Song of the South,” and a playlist like this one popped up. Ahem.) For a long time, the question I rolled around in my brain was not whether or not Song of the South was racist or offensive or wince-inducing to watch (and from the perspective of a cishet White guy, about as removed as possible from understanding the insensitive and vile nature of the stereotypes depicted in the film). It was whether or not the film deserved to be such a pariah.

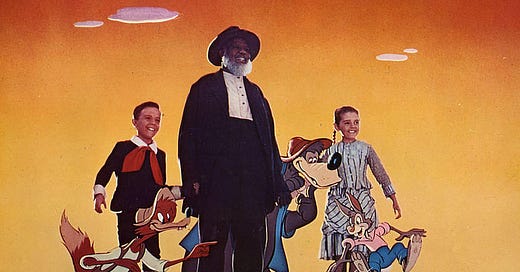

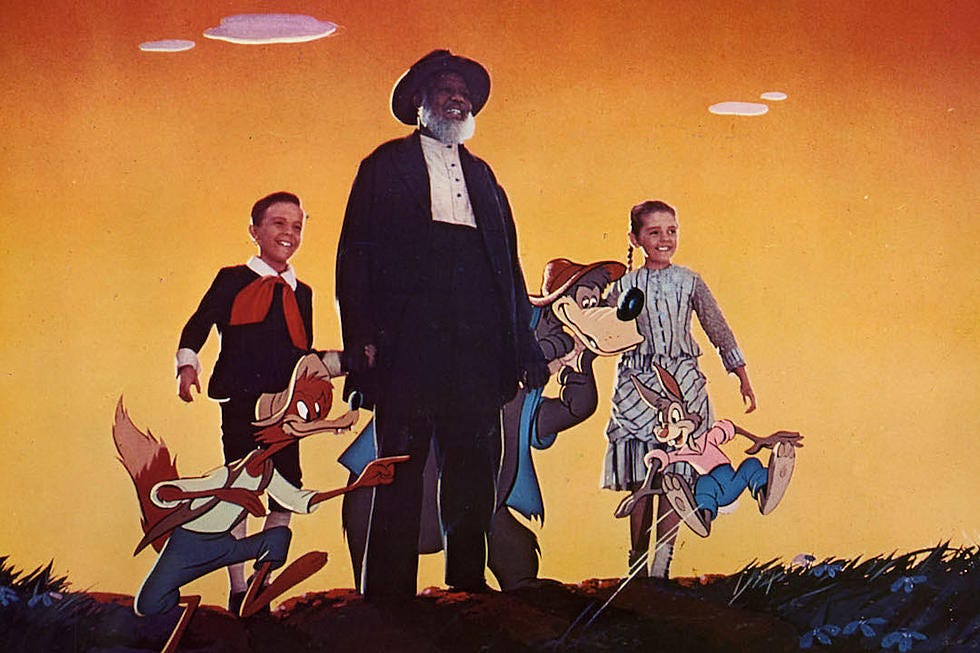

If you have not seen Song of the South (and if you do not take it upon yourself to click the link in the paragraph above), you probably only need to look at some of the images on this post to understand why Disney would rather pretend like this film never happened. The story of this movie is pretty thin: a boy named Johnny (Bobby Driscoll, a few years before he grew old enough to voice Peter Pan in Disney’s 1953 animated film) is brought by his mother (Ruth Warrick, who you may recall as Charles Foster Kane’s first wife in Citizen Kane) to his grandmother’s plantation. See, Johnny’s father is a newspaper editor in Atlanta who’s sown…some kind of controversy based on what he’s publishing, and Johnny’s mom wants to leave the big city behind for the time being. So Johnny has to make do on the plantation, quickly befriending the garrulous storyteller Uncle Remus (James Baskett), known for weaving stories of characters like Br’er Rabbit, Br’er Fox, and Br’er Bear. And coincidentally, a few of the stories Remus tells Johnny — of Br’er Rabbit visiting his laughin’ place, having an encounter with a “tar baby”, and more — line up well with Johnny’s frustration of being without his dad, of dealing with some nasty bullies, and of having a mom who’s very bothered by Remus telling her child life-lesson-teaching tales.

What makes Song of the South racist is not its pointed fixation on stories. (It is easy to wonder how much of Remus Walt Disney saw in himself, someone who just wanted to entertain those around him by telling stories that are meant to be fun, exciting, and might just have a moral or two embedded at the right moment.) It’s in the fact that this film takes place in the American South on a plantation, where all of the Black men, women, and children work as sharecroppers who seem to have no inner lives of their own except to do what the plantation owners wish for them to do. There is no violence in this story (aside from a climactic off-screen attack by a bull, and a couple of boys bullying Johnny), and technically it is not a depiction of slavery. I say “technically” because this film is set during the Reconstruction Era. I know this not because the film tells me via a title card establishing the year or the setting, but because Joel Chandler Harris (the White writer whose Uncle Remus stories are being adapted here) set his work after the Civil War. Y’know. Context.

Minute but important details like that are what this film’s defenders cling onto — it can’t be racist, they may argue, because Uncle Remus or Aunt Tempy (Oscar-winning actress Hattie McDaniel) are free to come and go as they please on the plantation. While that is…again, technically true, it is essentially impossible to watch portions of the film and not get a glimpse of something a lot more malevolent and uncomfortable, as when Johnny’s grandmother playfully tells Remus she’s not mad at him for telling his stories, or when Johnny’s mother constantly gets in Remus’ face for interacting with her son.

I should also note the vagueness of Johnny’s father departing for the majority of the film, not because of Driscoll’s intensely emotional reaction (though you can see why Walt Disney gravitated towards Driscoll as a child actor based on that scene). No, it’s because of the vague implication regarding Johnny’s father and the newspaper he works for. I would imagine that Johnny’s father working for an Atlanta newspaper may be a reference to Joel Chandler Harris having worked for decades at The Atlanta Constitution (now the Atlanta Journal-Constitution). Perhaps the idea is that Johnny’s father is a proponent of racial reconciliation, much as Harris purportedly was. But even the context of Harris’ hiring at the Constitution is grim when you learn that the man who hired Harris argued loudly for white supremacy, at a time when the latter was able to start crafting his immensely popular Uncle Remus stories (when they were published, at least).

A Disney film cannot, or perhaps should not, bear the brunt of all this history. Unlike, say, Pocahontas, the argument can be made that Song of the South is not inviting this amount of historical scrutiny. Though that may be true, it, too, feels pretty thin especially because the red flags existed when this film was made. Congressman Adam Clayton Powell (based in Harlem) condemned Song of the South as “an insult to American minorities”. There were protests in 1947 speaking out against the film. And it’s not as if the racism inherent in American society at the time was something to be ignored. Baskett, whose presence in Song of the South is effectively avuncular and charming (even as it is very reasonable to see his performance as a case of Uncle Tom-ism), wasn’t even allowed to attend the premiere of this movie. Why? Well, it was in Atlanta…which was racially segregated in 1946.

For all the many points of criticism I can levy at the Walt Disney Company of the 1940s, all circling around the obvious question — why make this movie at all? — I keep coming back to something else that Disney is known for that eventually bit it on the proverbial ass. Disney loves to self-mythologize. They love a legacy. I’ve talked before at the newsletter about how a number of the early Disney classics were not instant hits. (Dumbo, as fate would have it, was a success out of the box.) It’s only through aggressive re-releases over the decades that ensured modern audiences would think of Pinocchio or Fantasia, for example, as timeless and brilliant and enduringly popular. Song of the South was not a flop on its initial release — per Bob Thomas’s book Walt Disney: An American Original, the film netted a profit of $226,000 in 1940s-era dollars. But it, too, grew somewhat in stature through re-releases.

You may have noted above that this film was last re-released in 1986. 1986! It was released on the same weekend as An American Tail, and it was third! That re-release and whatever minimal pushback may or may not have existed led to the film’s presence at the Disney theme parks. Splash Mountain incorporated a lot of the animated elements of Song of the South — not just Br’er Rabbit and friends, but many of the songs that appear in those sequences as well as Br’er Rabbit being intentionally thrown into the briar patch to escape death. It notably did not include Uncle Remus. If you did not know the film, then, you would be able to avoid making connections between the ride and its source material.

Song of the South is not the only bad movie made by Walt Disney Animation Studios. (Though I do think the blend of live-action and animation is technologically impressive considering the era — and hey, the live-action cinematographer is Gregg Toland of Citizen Kane, so it looks great — this is a bad movie even if you can somehow ignore its inherent racism, because the story is soppy and obnoxious.) It is not the only racist film released by the studio. There used to be a part of me that wished fervently that Disney would release the film and handle it correctly. That part of me is long gone.

I’ll tell you why. It’s not that I think we should ignore this film, or that its historical import is not worth acknowledging. Consider a few facts. “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah” is an Oscar-winning song; it has been ranked by the American Film Institute as one of the 100 greatest songs in film history. James Baskett (who died in 1948) received an Honorary Oscar for his work as Uncle Remus, thus becoming the first male Black performer to win an Oscar. It’s not these details, or a discussion around the technology of this film.

To discuss this movie in depth should be to discuss it honestly and frankly, meaning without self-mythologizing. Disney can act like they announced the removal of Splash Mountain by sheer coincidence a month after police brutality protests began across the world, but to do so feels like an attempt to sidestep frankness and honesty. To be honest about this, they would need to be more timely. Context and timing matter. I know that Disney says stories matter too. But see, what I keep coming back to in my head is the fact that the Stories Matter website hasn’t actually done anything since it was posted three years ago. Three years ago, Disney made a very half-assed attempt to acknowledge that oh, sure, fine, a fair amount of their older films have some pretty embarrassing stuff in them. A title card that hasn’t changed in years, a website that also hasn’t changed, and a YouTube video from a diversity and inclusion initiative that has no other videos to its name…well, that’s not a whole lot.

To release Song of the South again now would require Disney to be honest with itself, to confront its past and acknowledge its mistakes. I don’t think it’s possible for them to be that honest.

Erasing historical films and stories that of the reconstruction era don’t erase the actual history. It’s my personal belief they allow for discussion that is necessary to teach about a history that did exist and how we can teach our children how we don’t want to repeat it. Again just my opinion but erasing the issue is more racist now. I could easily make the case that black America should be furious that the circumstances of the past area purposely being hidden from our youth. Feels like a missed opportunity to teach about cultural and racial progress in America.

Very interesting article, and it covers several topics I've discussed with my family before. I was lukewarm on Song of the South when I saw it in the theater--as you point out, the film isn't great--but did enjoy the ride. It was put together like most Disney rides were; the characters were bright, colorful, and thanks to the music that follows you everywhere on Disney property, the songs were familiar. That final splashdown was great, especially since the Magic Kingdom is short on thrill rides. But what was consciously omitted was painfully obvious, and even as a child, I wondered why the ride existed back when it was first introduced. Song of the South is one of those films that deserved to slide quietly into obscurity, but the controversy keeps it alive--so did the ride, which is why I'm not sorry to see it go.